The Life of Carina Ari (1897-1970)

Carina Jansson 1897

Carina 6 years

Carina 12 years

Carina as a Cossack, 1915

with Jean Börlin,

Royal Opera, Stockholm,1918

Carina ("Sylfide") 1917

Carina Ari 1921

Rolf de Maré at the Théâtre de Champs Elysées, Paris

Serge de Diaghilew (1872-1929), founder of Ballets Russes (the model on which Les Ballets Suédois was created)

Carina was a ballerina with an unusually wide-ranging talent. Moreover, she had what is called "stage presence", for lack of a better expression, an indefinable quality but nonetheless unmistakable. When Carina entered the stage, the audience pinned their attention on her, even if there were ten other dancers on stage, each with their individual choreographies (see, for example, Maison de Fous. This is an essential asset to any great performer, and those who have it seem to be born with it. In any case, there is no method to learn it. During her time with Les Ballets Suédois, Carina Ari made a name for herself in Paris, as in all the other cities the ensemble visited. Later on, she could return as a soloist and count on being remembered. She had "fans" everywhere (although the word had not been invented at the time).

Carina Ari 1925

Stadium ballets

Children's Day in Stockholm was usually celebrated at the Olympic Stadium with performances including a show by masses of dancing youths. In 1918, Fokine had produced a couple of spectacular colossal ballets: The Seasons and Moonlight Sonata. Obviously, there were not enough professional dancers and dance pupils to fill the enormous grass pitch. Therefore, school classes were engaged and trained especially to form movement collectives

The mass of participants and the simultaneousness had a strong ornamental effect. The principle of having many participants moving in unison is an old choreographic trick that has been used artistically in Swan Lake and La Bayadere, or more commercially by the attractive Tiller Girls, who were launched on the cabaret scene by the retired English sergeant, John Tiller.

Carina had, of course, seen Fokine's mass choreographies at the Stadium, perhaps even participated in them, and she was glad to manage the show in September 1923, when she had just become unemployed. The weather was clement, and her folk dance style show brought the house down. She was given the same assignment in 1929 and 1930, with more than 2,000 dancers, most of them children

"Colour Display", Stockholm Olympic Stadium, 1929

Carina Ari 1930

Rehersal of "Månstrålen"

with Serge Peretti, Camille Bos

and Carina Ari, left (1934)

Carina with her pupils in Paris, 1932 (top) 1933 (below)

Carina Ari as "Sulamit" in "Le Cantique des Cantiques", 1938

Carina Ari 1939

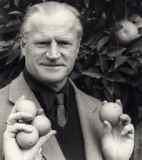

Jan Moltzer, Bols

Fruit for the drinks

Carina Ari 1950

Carina Ari with the bust of Opera director Harald André (1950)

Carina Ari, in the end of the 1960s

(Photo: Dagens Bild)

Carina Ari

(14th April 1897 - 24th December 1970)

The Will

In the conditions that Carina Ari herself dictated, she appointed a couple of personal friends whom she trusted to the board of directors for life. A few others were appointed for the period that they were active professionally in their respective dance-oriented positions, such as the director of the Royal Opera, a ballerina, a representative of the classical school, a representative from the Swedish Association of Dance Teachers and a member of the government.

The Swedish government undertook to supplement the board when needed and to ensure that the accounts were monitored by public accountants. Today, the Foundation is governed in accordance with the Foundation Act and the Board appoints new members when required.

The capital that Carina Ari left to her Memorial Foundation amounted to 12 million Swedish Crowns. Meanwhile, the capital has grown to approx. 100 million, making it one of the largest foundations in it's field.

Since the start, the Memorial Foundation has awarded thousands of scholarships to young dancers, supported some fifty older dancers on a more permanent basis, inspired an emerging interest in serious research subjects, and above all acquired a prominent position in the international efforts to salvage and maintain the immaterial cultural heritage of dance to posterity.

Written by Bengt Häger

Carina's life went through many changes. Born in a poor family, she eventually achieved fame, wealth and love.

Carina started her remarkable career at the Royal Opera in Stockholm. Her mother had entered her at the ballet school, which offered poor girls a chance to obtain free education. They also had the opportunity to earn an income even though they were children, since they often danced in the chorus at the evening opera performances.

All contributions were welcome in Carina's family. Her mother's health was poor, the identity of her father was never ascertained. Extreme poverty sometimes helps to sharpen the intellect. Carina bought flowers, arranged them tastefully, and sold her bouquets in Stockholm's Old Town to shopkeepers and craftsmen who used them to decorate their shop windows. She came up with this idea when she was 10 or 11. No one had thought of it before.

Fokine was an inspiring teacher

Ballet training at the Royal Opera was rigorous. Dancers became proficient in a rather stiff, classical 19th century style. The management did not have much understanding of choreography. Instead, dancers were treated as walk-ons by the opera directors. It was not until after the Second World War that dancers could devote themselves solely to the art of dancing itself.One person who opened up new roads at an early stage was the ingenious Michel Fokine, a regenerator of ballet, whom the Opera had judiciously brought to Stockholm for guest performances in 1913 and 1914.

The Swedish dancers found it enormously stimulating to learn from and interpret this great choreographer. However, two seasons after his short visit, the Opera ballet began once again to grow despondent.

The thought of a future without full artistic expression was unbearable to Carina. She had only recently succeeded in establishing herself as a soloist at the Opera, winning praise from Fokine himself, when she cast herself out into an uncertain future by giving in her notice. This was in 1918. Fokine had fled from the Russian Revolution and had opened a private school near Copenhagen. Carina persuaded a philanthropist (who was not particularly interested in danseuses) to give her the extraordinary sum of 5,000 Swedish kronor, enabling her to take private lessons from Fokine. The first ballet scholarship in Sweden, she called it. "It was my capital for life – what I learned from the master Fokine – both his new dramatic style of movement, and how to think as a choreographer."

Mauritz Stiller and "Erotikon"

Nevertheless, she was without a job when she returned to Stockholm. She gave lessons in ballroom dancing (a common, fairly well-paid occupation, even among classical dancers). At a dinner with the parents of one of her pupils, she met Mauritz Stiller, the film director who discovered Greta Garbo. "Erotikon" (Mauritz Stiller) 1920 At the time, he was working on a film in which the leading characters in one scene were in a box at the Opera. They needed something to watch, and it was causing problems. This was before the sound movie, and to show silent singers with gaping mouths, accompanied only by the usual cinema piano, might have had an unintentionally comic effect. Ballet was a much better choice. Stiller consulted the lady on his right. Luckily, she was free and could dance in his film. "But who will do the choreography?" he asked. "I can do that too," Carina assured him boldly. "I have a diploma from Fokine to prove that I'm a talented choreographer".And that is what happened. Stiller was unaware of the chance he was taking, and Carina understood exactly what was required. The choreography is straightforward, she adhered to Fokine's eastern style. Carina herself dances sensually in the leading role, in the manner characteristic of the exaggerated style of silent film. Carina's ballet in Stiller's film Erotikon (1920) is perhaps the only part of the film that is still worth seeing today

Carina continued to be a roving dancer without a permanent job. Then came the big leap forward! Out into the world!

The Ballets Suédois tour in Spain, 1921.

Jean Börlin, top, Carina Ari and Director Rolf de Maré below.

Jean and Carina have switched hats, but the "director" kept his own!

Paris - Ballets Suédois

After being persuaded by Fokine, the wealthy art collector Rolf de Maré, decided to follow the example of the magnificent ballet director Diaghilew (Ballets Russes) and earn a reputation in the snobbish Paris circles that rarely admitted foreigners. Carina was an obvious choice when the best and the youngest from the Stockholm Opera were engaged on three-year contracts in 1920 to tour Europe, with Paris as their base.

The Swedish ballet ensemble, Les Ballets Suédois (1920-25), was the world's second major private touring ballet, second in size only to Ballets Russes. This is worth bearing in mind, because fifty years later the world was full of similar dance ensembles. The dramatic theatres stay where they are and perform there. Dancers are constantly on the move. There is a natural explanation for this: Theatre can only be understood within the domain of its own language, whereas dance speaks a universal language without borders. In ballet, a major artist can change nationality without problem. Indisk tempeldans, 1920 That is what Carina Ari did. The girl from Old Town Stockholm transformed into a Frenchwoman and a pan-European star.

It all happened so fast. She became famous immediately, perhaps more generally and more unconditionally than any other dancer in Ballets Suédois. The choreographer Jean Börlin, a considerably greater artist, was more subject to debate. His radically innovative genius was hard to swallow, and his greatness was not obvious to everyone.

For Carina, the danseuse, Börlin's works were platforms from which she could show the multiple facets of an interpreting artist. Carina's range was far wider than that of most ballerinas. Initially trained in a pure, classical style, she had been coloured by Fokine's neo-romanticism (as in Sylphides or Jean Börlin's Chopiniana). She could also be grotesquely expressionist (as in Maison de Fous), unpretentiously folksy (Midsummer Wake), exquisitely elegant (Tombeau de Couperin), hilarious (Mariés de la tour Eiffel), and ever beautiful and sensual, with a twinkle in her eye.

The contract

Rolf de Maré had taken on all the dancers on three-year contracts, with full wages even in between seasons, when they had no audiences. Only a handful of state theatres offered such secure contracts. Coming from a private theatre director this was a generous deal. Up until modern days, the most common system has been to employ dancers for the limited number of performances procured by the management. In between engagements artists are left to fend for themselves – by finding another ensemble, living on savings or earning a living by some other means (waitressing in bars is common in the USA, for instance).Annual periods of unemployment are a problem that affects the lives of most dancers. But the members of Ballets Suédois could go off independently on vacation each summer, with full pay.

Carina Ari, however, had received an offer to take the leading part in a German film and had signed the contract, since it was to be shot during the first summer holiday of the Ballet. When she innocently mentioned this to Maré, he was furious. She was employed by him all the year and was not entitled to take other employment without first asking his permission. When he felt slighted he was implacable. The situation almost ended up in court, but Carina's solicitor advised her against it. She was forced to cancel the attractive film contract, which went to another unknown candidate by the name of Pola Negri. Her world fame dates from this film, which was a success. That fame could have been Carina Ari's. Her talent was at least as great. But a film star is always incomparably greater than a dancer, no matter how formidable, especially in financial terms.

Carina hated Maré for the damage he had caused her. Many years later, when she had become a grand lady and was much richer than he, she more or less forgave him. But whenever she had the opportunity she could not resist having a dig at him.

As soon as she could, Carina Ari left Ballets Suédois. Prior to that, she called in sick periodically, claiming to suffer from gout. There may have been some truth in this, but the attacks appear always to have occurred at convenient times. In general, she seems to have enjoyed excellent health and vitality throughout her life.

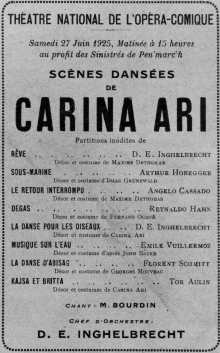

Inghelbrecht

In her feud with Rolf de Maré, Carina Ari was supported by his music director and senior conductor, Desiré-Émile Inghelbrecht. He was Debussy's favourite student and was to become one of the greatest French conductors of the 20th century.

Inghelbrecht was married to the daughter of the famous painter Steinlen (who did the stage sets for Ballets Suédois's production of Iberia). The marriage had dried up, and Carina took the place of Mme Inghelbrecht.

In the autumn of 1924, Inghelbrecht became the music director of Opéra Comique, the second state-run lyrical theatre in Paris, which specialised in dramatic, medium-sized operas, such as Carmen. French taste demanded that each opera featured a ballet, but pure ballets were reserved for the Paris Opera at that time. For many years, Carina Ari worked on a risky plan of setting up a full evening programme, featuring herself, not only as sole choreographer but also as the only performer.

Although this was common practice in the new genre of Modern Dance (also called Free Dance, i.e., free from classical rules), no classical dancer had dared to do this before Carina Ari. In common with the "free dancers", Carina's opportunities to perform were few and far between. She only had steady contracts during a few relatively short periods in her career.

Despite her faithful performances of Jean Börlin's innovative works, which were far ahead of their time (they have not been fully understood in a historical perspective until now, in the days of Pina Bausch and Alvin Nikolai) Carina Ari was not at all interested in going against the classical tradition.

She was a devout disciple of Fokine in every respect, including the more practical aspect of his reforms – to create a programme with such variation that it would satisfy the new 20th century restlessness. The long performances of the previous century, such as La Bayadere, Le Corsaire, even Sleeping Beauty, were stories with complicated plots that were told with literary meticulousness. Only a few were sufficiently poetic or psychological to be captivating or even entirely comprehensible (like Swan Lake and Giselle).

Fokine's concept was ingenious in its simplicity: a ballet should not be longer than necessary. One act usually suffices to express what needs to be said. A bouquet of short ballets enables more variation. The Ballets Russes programme usually comprised several short pieces, and so did the Börlin repertoire for Ballets Suédois. A large portion of the success of these artistic innovators is also attributable to their imposing stage sets, a new one for each piece. The audience did not have time to grow weary of one setting, before it had given way to a new one.

Carina Ari made note of this. Instead of the unadorned stage draped in dark curtains favoured by modern dancers, according to the style launched by Isadora Duncan, she had large scenographies painted for each of her solo dances. She had befriended several prominent painters, and Grünewald, Moreau and Dethomas painted her sets free of charge. Inghelbrecht's circle of friends included the composers Honneger, Reynaldo Hahn and Florent Schmitt. These composers and her husband delivered the music. Carina danced to a 40-piece orchestra conducted by Inghelbrecht – not to a solo piano, which was what most of her colleagues had to make do with. Carina Ari presented her eight "dance scenes" in 1925 at the Opéra Comique.

The first piece is Rêve, a poetic idealisation that expressed a longing to become a tree in nature. This is followed by Sous-marine, an underwater scene with billowing seaweed fighting for survival. The next ballet is Le Retour Interrompu, set outside an inn in a Spanish village. A girl passes by, but stops when she hears music through a window, dances by herself and then continues on her way in the night. Degas is a humorous rendering of the life of a classical dancer, barre exercise, flirting with admirers, precious dancing – a satire on the airs and mannerisms of a ballerina. Carina herself made the sets for La danse pour les oiseaux, in which she used the classical style in earnest, illustrating birds and their flight. Musique sur l'eau comprises both the sea waves and a mermaid swimming with her winged sisters, the swallows. La danse d'Abisag tells a biblical anecdote. The figure of a virgin emerges from a Byzantine wall and dances for the aged King David, with cubist, angular movements, restrained and archaic – the most original piece in the series, in terms of style. A more light-hearted finale is afforded by Kajsa et Britta a bagatelle about how "the clothes maketh the girl". A poor girl borrows an outfit from a rich girl and is suddenly pursued by every boy.

A complex programme – and Carina did not take the easy way out with regard to practical matters. She did not want to fill out the pauses between dances with music. Therefore, each set had to be changed with lightning speed. She had a maximum of two minutes in which to change costumes. Every detail was worked out meticulously, and costumes were constructed after extensive experiments. But the most demanding part was the enormous concentration required to shift immediately from one state of mind to another. The audience was in raptures over Carina Ari. She continued to perform her dance scenes in Paris and made guest performances in the rest of Europe, including Stockholm, as a "one-woman tour" together with Inghelbrecht, who rehearsed with a new orchestra at each new venue.

Ode à la Rose

In connection with celebrations at the Presidential Palace in Paris in 1927, Carina Ari was honourably commissioned to produce a choreography for a temporary dance troupe. She wrote Ode à la Rose, based on a poem by Ronsard. It is an ode to the flower that is such an essential symbol in the emotional world of troubadour poetry. Carina Ari was drawn to such subtle, almost abstract emotional renderings.Following her acclaimed Rose ballet, Carina Ari was commissioned to create a ballet for the Paris Opera itself – Palais Garnier, as the Parisians call it, in commemoration of the architect (how many Stockholmers know who built the Royal Opera in Stockholm?). The Paris Opera ballet had fallen into decline at the turn of the century. It had been outshone first by the Russians, and then by the Swedes, it had stagnated, was out of touch with the times, and was looked down upon both by the theatre management and the audience. Therefore, it was no longer allowed to produce its own programmes but was merely used to fill out the gaps when an opera was too short. It was not until 1930, when Serge Lifar was engaged as ballet director, that the Paris Ballet was substantially regenerated and achieved a new greatness that has lasted until our days.

The first ray of hope was delivered by Carina Ari, with her ballet The Moonbeam from 1928. She arrived at the right time. These dancers were trained to perfection in classical dance technique. What they needed was an injection of new life, with a suitable choreography. Carina Ari described The Moonbeam as "a choreographic poem". To be on the safe side, she painted the sets herself. Masses of her small sketches still exist. She prepared the composition and painted virtually in detail every change in the dancers' movement and distribution across the stage. In other words, she created her own notation system. If Börlin had taken the time to do this, we could have studied his pioneering works and recreated them with greater authenticity today!

With impeccable taste, Inghelbrecht chose music by Gabriel Fauré and orchestrated it himself. The ballet has the vestiges of a "narrative", but it is highly abstract, consisting of visions, allusions and ideas, rather than a clear story – a mild rivalry between the Moonbeam, who wins the Youth from the Daughter of the Blue Mountains, but has second thoughts and returns him to the one who best deserves him. Winds, skies in paler or darker nuances, glide over the stage with exquisitely shifting lights (composed by the opera director Rouché himself). The Moonbeam is related to Fokine's Sylphides, but is much more subtle – and with an undercurrent of sensuality.

There are remarkably few women choreographers in the history of French classical ballet. Among the few, two were born in Stockholm: Marie Taglioni, who created her only ballet, Le Papillon, in 1860, and Carina Ari with her Moonbeam in 1928. I have not seen the former, but descriptions of it give the impression that there are similarities – both are lyrical phantasms, both are illuminated by the "mysterious" moonlight.

The Moonbeam was yet another lauded success in Carina Ari's row of similar triumphs. It was produced again in 1934. She had created the leading part for Spessivtseva (one of the greatest dancers of the time), but she had an accident, and there was very little time to find another dancer who was capable of dancing the highly original part. Therefore, Carina Ari had to do it herself in 1928, and she also performed the part when the performance reopened in 1934.

Short guest performance in Algiers

The Opera in Algiers was in dire need of substantial artistic regeneration. By this time, Carina had earned a good reputation among professionals, and she was taken on as ballet director, with Inghelbrecht as director of the Opera.

In Algiers, the opera pandered to a wealthy, conservative, French bourgeoisie. Inghelbrecht, a passionate enemy to any form of racism, succeeded in almost immediately antagonising most of the community, and returned in a fury to Paris. Carina had already invested a great deal of work in regenerating the ballet and had recruited new dancers from Den Kongelige Ballet in Copenhagen, where her former colleague from Ballets Suédois, Kaj Smitt, was the ballet master. In the first season alone, Carina produced six of her own ballets, in addition to new choreographies for all the operas on the repertoire.

After a year, she grew ill with exhaustion and returned to Inghelbrecht in Paris. They were both contracted in 1932 to the Opéra Comique, he as music director, and Carina Ari as an "étoile" (i.e. a star ballerina on a par with those of the Paris Opera), and director of the Ballet. She had the enormous task of revising all the dance pieces for the opera, which in effect meant composing new ones. She was praised in the press for these "masterpieces of taste and wit". The Opéra Comique still regarded independent ballets to be superfluous. Carina managed to get permission to do a ballet based on Brahms waltzes in a more or less abstract style (that Balanchine was later to devote himself to).

Currents in the world of ballet

In the early 1930s, it was till customary to let older, sturdier ballerinas perform the male parts in travesty. This practise was disliked by Carina Ari, who always loved men.

She advertised for male dancers, especially a partner for herself. Balanchine applied but was rejected. He was never particularly proficient as a dancer, although he was later to become one of the century's greatest choreographers. Instead, she chose Boris Kniaseff as her partner. He was no great dancer either, but great male dancers were rare. Kniaseff eventually came to be an excellent teacher and was head of the Royal Opera ballet in Stockholm for a period in the 1940s.

This brings up another side of Carina Ari's work that appears to have been all but forgotten. She had a great talent for teaching. As mentioned, she was a private pupil of Fokine's, after having been schooled in the classical French style at the Royal Opera ballet school in Stockholm. Her second in command at Opéra Comique was a slightly older dancer, Mauricette Cébron, who adhered to Carina's methods and conducted the daily practice sessions when Carina was too busy. In 1934, she left Opéra Comique to become a teacher at the ballet school of the Paris Opera for a quarter of a century. Nearly all subsequent famous French stars started by studying for her, and according to a system that emanated from Carina Ari, that she in her turn had adopted from Russia, which in turn had been influenced by France and Italy. That is the way the currents may flow in the world of ballet. Carina was a link in the chain, a vital link.

Inghelbrecht and Carina Ari stayed with Opéra Comique for less than two years. As mentioned, Carina went on to stage a new production of The Moonbeam at the Paris Opera, followed by the Royal Opera in Stockholm in 1935. The following year, she staged a first performance in Stockholm of the ballet Eva (properly titled The Metamorphoses of Eve), a medley of Eves through the ages, offering some rewarding roles for the Opera soloists.

The première dancer Teddy Rhodin of the Opera ballet wrote in his memoirs, "I had never seen anyone as beautiful as her."

A year later, just before New Year's Eve 1937/38, Carina performed Ode à la Rose at the Stockholm Opera, substantially extended into three pieces that together formed a full "Carina Ari Soirée".

A quarter of a century went by before she returned with a new choreography to the town where she was born – a reconstruction, to the best of her memory, of Börlin's The Foolish Virgins. By then, she had entirely forgotten her own choreographies. This is not an unusual phenomenon among choreographers.

Carina Ari, Serge Lifar, Paul Goubé

Le Cantique des Cantiques

Yet another significant contribution lay before her in the 1930s in Paris. Serge Lifar wanted to create a ballet based on the Song of Solomon from the Bible, Le Cantique de Cantiques. He took the leading part himself, and needed a partner.The piece was one of Lifar's modernist experiments. That kind of experiment was a thing of the past – modernism had culminated in Paris in the 1920s, with Ballets Russes and Ballets Suédois and the plethora of "isms" surrounding them. The looming war that was foreboded by many created a cold climate in 1938. The ranks of artists and models at Café Dôme started thinning out. Only the ballet seemed impervious – until after it broke loose. The music for Cantique des Cantiques was commissioned from Honneger and consisted mainly of percussion. the role of Sulamit required a skilled dancer with classical schooling but the ability to disregard tradition and move "freely", sensually and at her own discretion. Lifar could find no one with these qualities, apart from Carina. He created an approximate choreography, and his intention was that he alone would improvise, in order to achieve a special tension, a moment of creation right in front of the audience. Carina was not informed of this, but in their main pas de deux he started to move differently from how they had rehearsed together. What was she to do? "I couldn't just stand there with the audience gaping at me!" With death-defying courage, Carina choreographed herself – literally as she stood – to accompany her partner, and it eventually developed into a battle of who could be the most expressive.

No one could equal Carina's rhythmic and musical talent. The audience cheered and the press was exultant about the danseuse – and slightly less so about the danseur. However, Lifar benefited too. Cantique des Cantique went down in history as one of his most remarkable works. But after eight performances, Lifar had had enough of choreographic duelling and closed down the performance

Only once more, in March 1939, did Carina Ari perform her "Scènes dansées" at the Opéra Comique. It was to be her swan song.

A dominant husband

The farewell to the stage is the most painful moment of a dancer's life. It is far worse than for other artists. Carina was still so young, in her early 40s, the best years of a woman's life. And yet, it was perfectly normal and unavoidable that her muscles started rebelling against her soul's craving to dance.

Carina was an extrovert and exhibitionist, like all real dance artists. Long ago, she had learned a skill that had become second nature. Moreover, Carina had been the centre of attraction, drawing the attention of thousands, governing the audience's emotions, arousing and seducing men and women, young and old, throughout her entire adult life.

When it is at its best, it ceases abruptly. It gives a foretaste of death, although half one's life remains. Carina always shrank from the mere thought of death.

This is a phase when dancers are extremely vulnerable. Most of all, perhaps, they need the love and care of a partner. For Carina, this love had been gradually slipping away from her. Inghelbrecht, who had never been particularly warm-hearted in either of his marriages, fell madly in love for the first time in his life, at the age of 60, with Carina's best friend. Carina herself had always been prone to fall in love easily, and her candid "affairs", some short, some long, sometimes with more than one lover at a time, had never troubled Inghelbrecht in the slightest. He sometimes referred indulgently to Carina as his daughter (which she could have been, with regard to the age difference).

For the first time, Carina grew aware of feeling lonely. She fled the fashionable Paris circles and travelled to a sleepy, luxurious spa, Aix les Bains, under the pretence that her muscles ached (a psychosomatic complaint rather than a real one – she enjoyed robust health). As usual, she had no money. She had never before needed to pay her own way, and had always been able to rely on her rich and generous friends.

The same was true now. A friend invited her to dinner at the finest spa hotel in Aix. Carina dressed (with her usual apparent simplicity, intended to cause a commotion) in a full-length white dress and a small red bolero. Her entrance into the restaurant was magnificent. The waiters lost their bearings and nearly dropped their trays. A short, nondescript gentleman at one of the tables totally lost his head. Very soon, he had invited her to his table for dinner. He was reluctant to reveal anything about himself. He was Dutch, extremely intelligent, accustomed to giving orders, but currently in a state of shock, because his wife had tired of him and had filed for divorce.

Mr Moltzer was colourless, short like Inghelbrecht, but sturdy and muscular, with a handsome, strong head. He was reticent and secretive. Carina was exquisitely beautiful and slightly buxom (since she had stopped ballet practice), outspoken, humorous, sensual and generous with the only thing she had left – her body and her strong spirit.

That is how they perceived one another. He asked if she would accompany him to South America to live. Marriage was out of the question, at least for the time being, since his ex-wife had discovered that her discarded husband had found new happiness. The divorce proceedings were protracted to punish him, and it was expensive. The legal marriage between Jan Moltzer (his third) and Carina Ari (her second) had to wait until 1942.

Carina eventually found out more about the new man in her life. He was a son of a Dutch industrial magnate, and had inherited the old noble beverages company Bols. Moltzer foresaw the war with Germany. Perhaps he was not entirely Arian according to the Nazi definition. In any case, he took his best foreman with him to the Buenos Aires distillery and was able to supply his genuine famous alcoholic products to the entire free world throughout the war, when other industries in Europe were prevented from doing so. Both his sons died in the German occupation of the Netherlands, and one of his daughters was a close friend of her stepmother to the end of her life. Carina and Jan Moltzer never had children, but they did have a very happy ten-year marriage.

Carina enjoyed having a dominant husband, she liked men who were strong and virile. Moltzer was not particularly funny, but he was kind. He loved her prodigiously in his own magnificent way, showering her with costly jewellery and furs. He hated hesitation. If they were in a shop and Carina enjoyed the pleasure of trying on half the stock, as some women do, he would burst out, "Do you want the one you've got on? Otherwise, we'll leave at once!" Quick-witted as she was, Carina soon learned to say yes, just in case. She could always have another fur coat later if it wasn't entirely to her taste.

Carina grew to be a superb hostess at Moltzer's mansion-like residence outside Buenos Aires. She was naturally theatrical, a primadonna from head to toe, and at the same time refined, tastefully unassuming and always sympathetic to other people's worries.

Jan Moltzer died of a heart attack in 1951, when he was only 68 years old. His widow inherited a large portion of his fortune, which was mainly invested in shares in Bols companies. Carina grieved her departed husband deeply and sincerely. She was 54, and never again fell in love.

Dancing was a finished chapter. Like many ballerinas, Carina had the urge to sculpt, in order to have a creative outlet. She studied in New York, among other places, and became proficient in sculpting portraits, mainly of her friends. Her large portrait of Dag Hammarskjöld is one of her most successful works. It now stands at the UN headquarters in New York and at Uppsala Palace in Sweden, where he lived when he was young.

After the death of her husband, Carina Ari de Moltzer remained in Buenos Aires, where she had gained many friends and was the centre of an intense social life. Once every two years, she would visit Europe. She kept her beautiful little studio flat in Paris, and the crayfish season demanded a visit to Stockholm. She sometimes also spent part of the summer in Sweden.

The Donatrix

With the exception of a few personal friends in Stockholm from before the war, remarkably few had heard of Carina in the city where she was born. Twenty years had passed since her dance performance, and the Second World War was also a mighty watershed between old and new. Dancers are easily forgotten, possibly due to their short careers – they retire while still young.

An extensive marketing campaign was needed to revive Carina Ari's name in the media consciousness. But once this had been done, she became more famous than ever before. She experienced great pleasure (with a characteristic wry scepticism) in becoming a superstar. In fact, it was easy to achieve – her great charm made her unforgettable to anyone who met her, not least to journalists.

Carina used to say that the money she had received in her youth to pay for studies with Fokine gave her the break she needed. She wanted to give latter-day colleagues the same chance. Not that she under-estimated Swedish dance teachers. On the contrary, the Swedish Association of Dance Teachers was included in her extensive charity. However, dance is the most international art form, and it is an effective stimulant to new artists to have the opportunity to travel abroad and see how people dance in other cities, and also to try studying at a dance school in another country, as a change or a complement.

She started a scholarship foundation. Friends of dance founded an award in her name, to be given to people who have been "a credit to the Swedish art of dancing". The Award has been frugally given since it was instituted in 1961.

Sweden already had a dance museum that was unique in the world, created in memory of Rolf de Maré. Carina asked me if there was anything she could do on a par with this museum. An institution that would benefit dance and make her name live on.

What could be more vital than a large library with literature about dance from the entire world? She decided to start the Carina Ari Library, which today is the largest in its field in Northern Europe, and with sufficient capital for acquisitions and maintenance.

Carina had no remaining blood relatives. There was no one on her mother's side, and the identity of her father had never been confirmed. One of the last times she was in Sweden, she was called to a country hospital, where she visited an old man on his deathbed. What they spoke about has never been revealed, but her closest friends were convinced that this was her father, who had periodically lived in her home when she was a child.

Carina was terrified of death, but realised that something must be done about the fortune she would leave behind. A will had to be written, to outline her intentions, and to provide the best possible guarantee that the funds would last forever. One of her best friends was the then Swedish Minister of Justice, Herman Kling. Under his auspices, the will was written by the most skilled solicitor he could find. A new foundation was established to serve as her sole heir. The Carina Ari Memorial Foundation was dedicated to three purposes: to award scholarships to young dancers for studies abroad, to support deserving elderly dancers, especially in connection with illness, and to encourage research in the field of dance. The task of awarding the Carina Ari Medal was transferred to the Memorial Foundation in 2016 and thereby became the Foundation's fourth purpose.

In the autumn of 1970, Carina broke her thigh in Buenos Aires. Doctors consider this a relatively minor medical condition, but her resistance was low due to diabetes. She was operated on, but the incision would not heal. After a long struggle, her brave dancer's heart gave up, on Christmas Eve 1970. She rests alongside her husband in one of the most beautiful cemeteries in Holland.

Bengt Häger

Bengt Häger with Carina Ari (1966)

På Svenska

På Svenska In English

In English Auf Deutsch

Auf Deutsch En Français

En Français In het Nederlands

In het Nederlands